The following contains spoilers for The Penguin #1, on sale now from DC Comics.

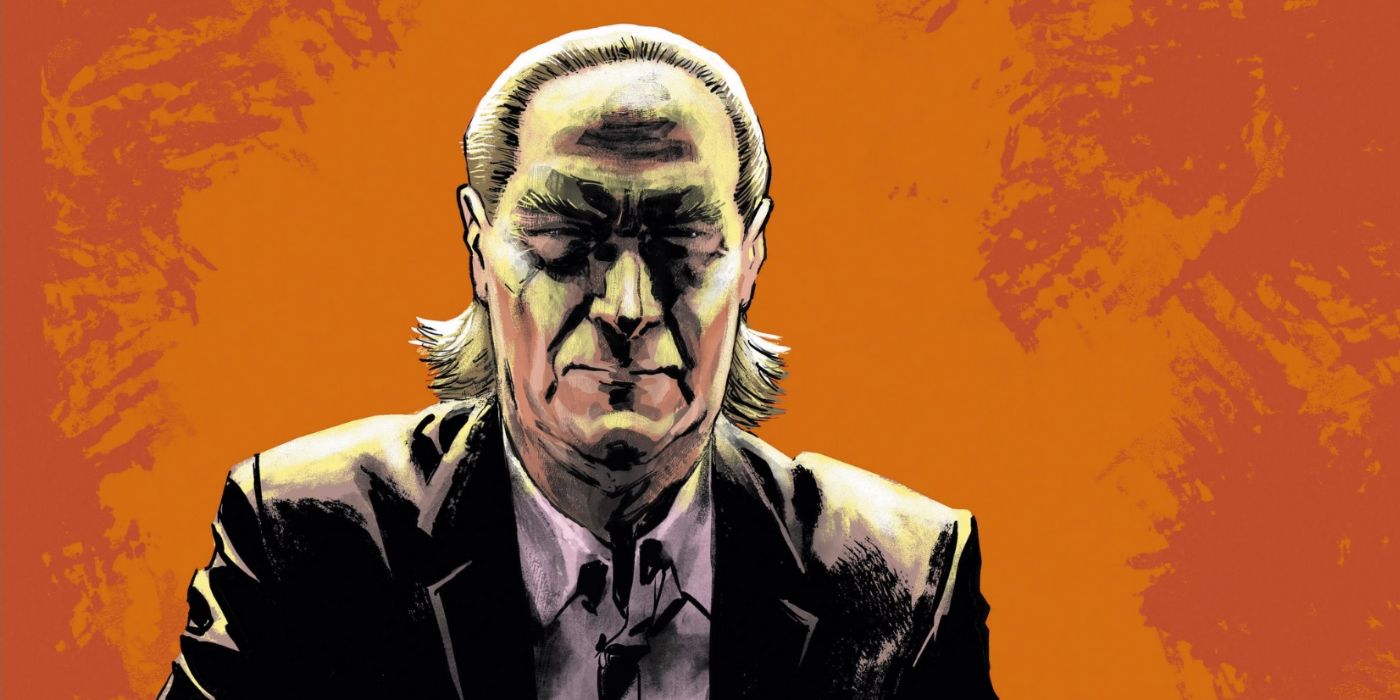

DC’s The Penguin #1 (by Tom King, Rafael De Latorre, Marcelo Maiolo, and Clayton Cowles) marks a tonal overhaul for Oswald Cobblepot. Plastic surgery has reduced his trademark crane-like nose, bringing him closer to his cinematic counterpart as portrayed by Colin Farel. The more brutal and mafioso-styled aspects of his crimes and personality have taken center stage over campier antics, and blood is splattered semi-regularly. All this serves to explore the Penguin in a more mature setting than he has previously been afforded.

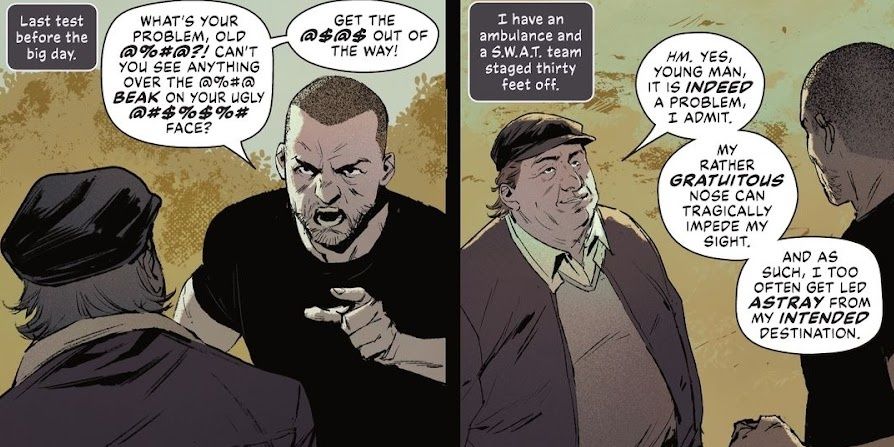

To really bring home just how mature The Penguin is, every other character has a string of profanity to express. Yet with this being a mainstream DC publication, those expletives have all been replaced with @#$%. While @#$% has its place in comics, especially humorous ones, it can often undercut the established tone of a serious story. An excess of profanity alone can additionally signify the degradation of someone’s resolve. Here, it seems that this fact might actually be an intentional part of Tom King’s narrative.

What Is “Grawlix” and How Does it Work?

The usage of symbols in place of profanity in comics is often believed to have begun around 1902. These instances are credited to the newspaper strips Lady Bountiful (by Gene Carr) and The Katzenjammer Kids (by Rudolph Dirks). Astonishingly, Lightning Flashes and Electric Dashes (by James J. Calahan) implemented the trick even further back, in 1877. This compilation of musings about the then-rising telegraph industry replaced various verbal expressions of displeasure with mostly asterisks and exclamation marks but few other symbols.

It would take time for the practice to develop into how it is written out today. Mort Walker, the creator of Beetle Bailey, wouldn’t coin the term “grawlix” to describe this phenomenon until 1964. A grawlix on its own does not represent one word in particular. It may even represent the presence of profanity rather than any one decipherable term. There is no specific way to depict a grawlix as its symbols may be placed in any order.

A grawlix’ characters often consist of @#$%^&* but, given their pictorial nature, can include whatever the author wishes. Pre-existing additions include a sailor’s anchor and a fizzing cartoon bomb. The anchor has been noted by many to evoke “cursing like a sailor,” while a bomb can connotate the explosiveness of an outburst.

Grawlix Turns Profanity Into a Theme in The Penguin

In The Penguin #1, government agent Nuri Espinoza details her five-year recovery process after being shot in the head in Batman: Killing Time (by King, David Marquez, Alejandro Sanchez, and Cowles). She had been so prone to profanity prior to the incident that afterward, along with not being able to walk or eat properly, she could only say curse words and “Batman.” Others, including Amanda Waller, had taken to calling her Agent #$@%@. She then grabbed the biggest dictionary she could and swore never to use profanity again as an integral part of her recovery.

Espinoza successfully forces Penguin into reclaiming his criminal empire. Eventually, her fear and adrenaline hit a tipping point, and despite all her discipline the agent finally yells out “@$%#@$!” in excitement over having positioned such a man into working for the government. Since this was achieved by abducting his wife, she knows he will likely kill her. The Penguin thus uses Espinoza’s deference to profanity to highlight the habit as a product of base emotion. Simultaneously, the size of her exclamation on the page brings attention to grawlix’ other uses in the story. This turns the reductive practice into a theme that is a larger problem in mainstream superhero publications.

Grawlix Can Undermine the Tone of an Entire Story

Traditionally, grawlixes have been used to mostly comedic effect. They are typographically akin to a cartoon character saying “razzum frazzum” while falling closer to a bleep effect. In many cases, the usage of a grawlix may be the comedic punch itself. In The Penguin, everyone who uses excessive profanity does so from a place of either fear or anger. Replacing these words with grawlixes is a way to visualize the undermining of their own integrity.

Grawlixes can undermine entire scenes that otherwise exist to convince the reader of how dramatic the stakes are. Their inherent function of cartoonifying dialogue renders naturalistic “adult” language silly the moment it’s spoken. It also prompts a greater interest in younger readers to figure out what those unused words are. It can be reasonably argued that using the words outright would be more honest to storytelling efforts while making less of a deal out of them. At the same time, not having that self-censorship would lead authors to be a lot more conscientious of how much profanity is necessary to tell a particular story.

There Is a Proper Time and Place for Grawlix

There is of course a time and place for grawlixes in contemporary storytelling. Children’s comics benefit greatly when they need to show that a child has learned a word they shouldn’t repeat. More traditionally, an author might wish to illustrate an older character’s anger in a quick and comedic manner. Grawlix can also benefit a slightly more mature audience. It can counter machismo when it comes to selling the mood for over-the-top action, and can be given to protagonists while handing intentionally excessive gore to establish a comedic balance.

There is also room for grawlix to be implemented ironically. Yet the focus of self-censorship remains on the exposure of words and not the surrounding actions, which can be equally brutal (if not moreso) in The Penguin. This has the effect of revealing a cast so accustomed to the atrocities they enact and witness that the tamest offense possible has become the last method of retaining any sense of innocence within themselves.